Late Soviet Queer and Feminist Temporalities

Notes on Queer Socialism and the Paradoxes of Soviet Feminism

What do queerness and feminism mean in capitalism? Do they mean the same thing in communism? How do temporalities shape the meaning of queerness and feminism and vice versa? These are some of the questions we set out to explore in our sessions on queer and feminist temporalities on 26 March and 7 May 2024, curated by Bogdan Ovcharuk and Anya Kuteleva.

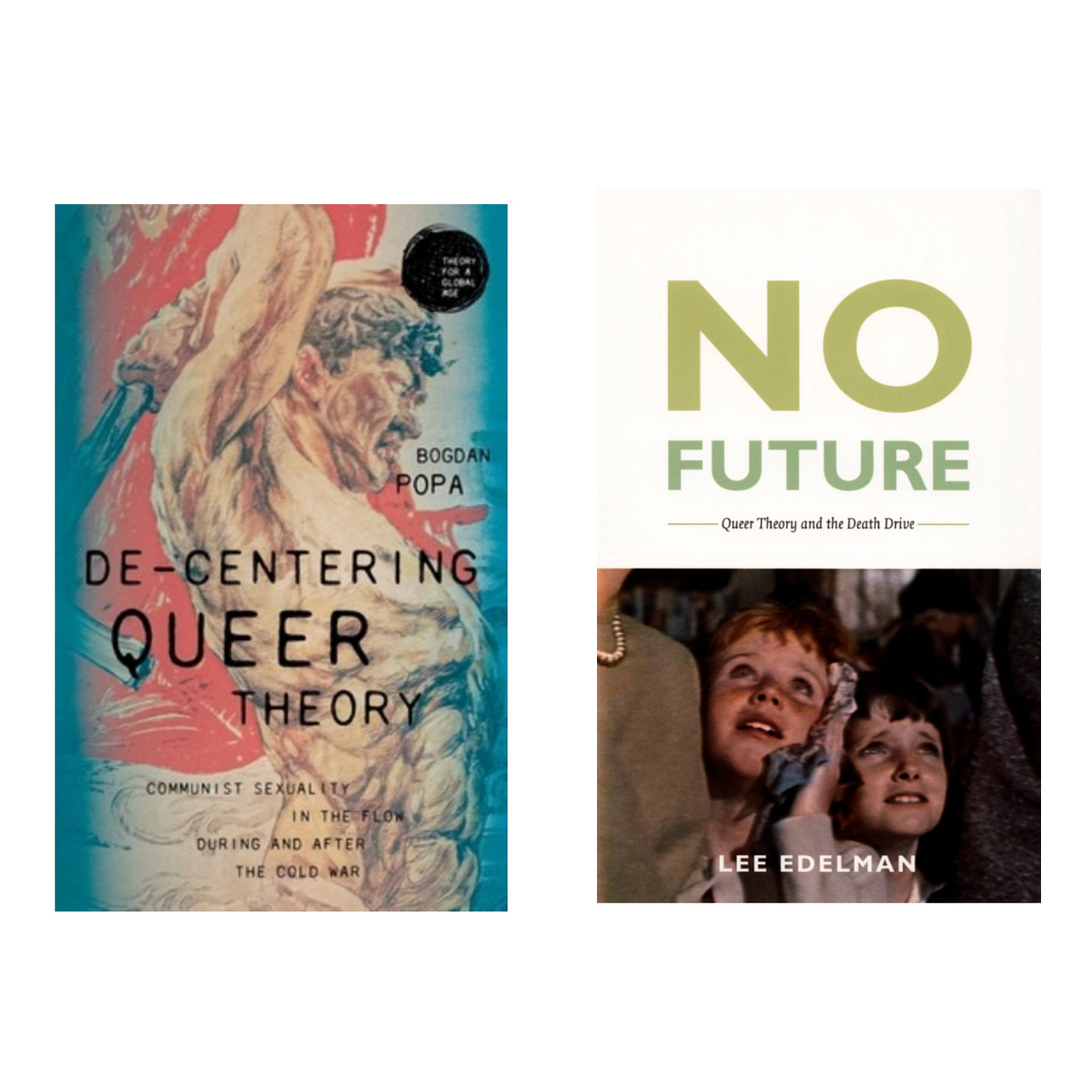

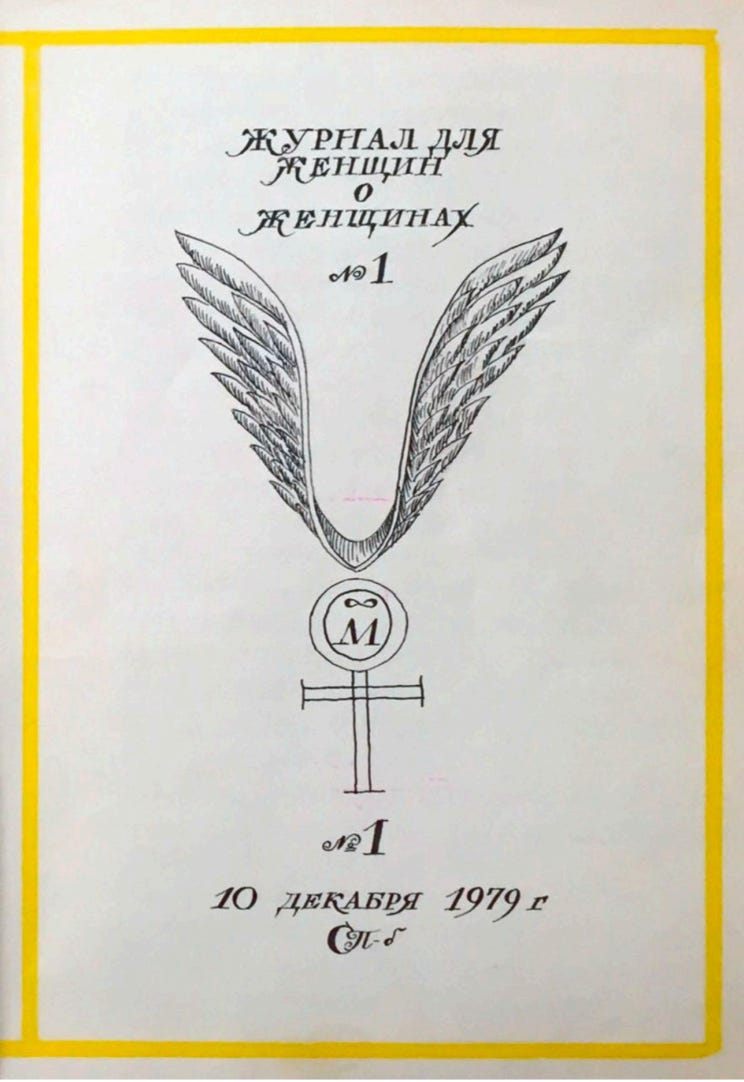

To think about queerness and time, Bogdan invited us to read the first chapter from Lee Edelman's No Future (2004), titled ‘The Future is Kid Stuff,’ and selected chapters from Bogdan Popa's De-centering Queer Theory: Communist Sexuality in the Flow During and After the Cold War (2021). With regard to feminist temporalities, Anya introduced us to the first feminist samizdat journal in the Soviet Union, Woman and Russia, published in Leningrad in 1979. We discussed Natalia Malakhovskaya's essay ‘The Matriarchal Family’ (1979), coupled with Asya Khodyreva's ‘Samizdat “Woman and Russia”: For the 40th Anniversary of the Late and Post-Soviet Feminist Tradition in Russia’ (2020). We used these texts as springboards for interrogating the relation between socialism and queer bodies, gender and time, and the paradoxes of late Soviet feminism.

“Queer Socialism”

In his thought-provoking introduction to queer temporalities, Bogdan Ovcharuk succinctly summarised the contrast between the two texts as one between ‘the perennial queer transgression and the materialist critique on the terrain of queer theory itself.’ While Lee Edelman’s work has become a seminal contribution to the queer theory canon, Bogdan Popa’s book, ‘one hopes, is yet to make its waves in the discipline.’ Working in the psychoanalytic tradition, Edelman's postmodern Lacanian intervention is, as Bogdan put it, at times ‘unsettling in its asociality.’ The obvious contrast between the two lies in that, ‘unlike Edelman, Popa presents a historically grounded, materialist, and Marxist intervention into the canon of Western queer theory. Importantly, the experience of Eastern socialism is revealed in its queer aspect, tempering the hubris among Western literati to dismiss this experience as occurring, as it were, before gender and sexual liberation.’

Juxtaposing the two texts, Bogdan’s introduction flagged some important thematic points that guided our conversation throughout. Below we recycle verbatim some of the most important points that Bogdan raised:

The infamous Child — that re-productivist emblem that Edelman would have us kill

The notion of ‘radical futurities’ has become the hallmark of utopian and abstract thinking that characterizes so much of postmodern scholarship. Edelman does not engage in a critique neither of the liberal emphasis on ‘infinite progress’ nor on its sexy postmodern cousin — radical queer futurity. Instead, he explicitly argues against any ‘negation of negation,’ any determination through reflexivity and dialectical revelation of meaning. With the tools of Lacanian psychoanalysis, we are given pure negation — the death drive that is just as infinite as the future it seeks to counter. But in refusing to argue against the abstract negation of the present for a radical future, does Edelman miss an opportunity to inaugurate a turn against future utopia through a determinate negation, that is, a critical analysis of actuality and its real emancipatory possibilities?

The emergence of natalism

Popa interprets it as an attack on the socialist productive body. In his historical analysis, he shows how the Western conservative emphasis on productivism was introduced to the socialist world at the point of its opening up to Western epistemology during the Thaw period. Anti-abortion, reproductivist themes in late Romanian film production are shown to be emblematic of the shift from communist transformation to producing more children for the State. It is as a result of this Western conservative and post-WWII Cold War epistemological influence that Alexandra Kollontai's emphasis on the collective and erotic process of constituting a new society was replaced with the individual and natalist love of two heterosexual individuals.

Productivism in Popa vs Edelman's politics of futurity

Popa’s productivism is part of a dialectical and emancipatory project to abolish capitalist sex roles. Drawing on Soviet Marxism, in particular Bogdanov and Arvatov, Popa shows that the productivist body generates a dialectical and collective process to affirm use-value and achieve communism. Popa writes: “Socialism produces human subjectivities for their social value, as opposed to US social science’s emphasis on the social that constructs a given body and personality.” For Soviet Marxists, “productive labor was to be ‘the foundation of the educational process’ and the development of the communist child.” This is meant to counter the social constructivism of Western continental theory, with its emphasis on language as the irreducible basis of social reality.

Abolition of capitalism

Popa's 'abolitionist' standpoint does not seek to abolish the world, but to abolish capitalism for an Enlightened sociality where our social interactions are tied to radical needs, both material and erotic, but always counter-fetishistic. This contrasts with the emphasis on the death drive. What is curious is that the negativity of the death drive, for Edelman, echoes the law's foundational act. There is something Heideggerian and in this emphasis on the constituent power of the death drive which is simultaneously destroying, what Heidegger calls the uncanny power of the polis which is also apolis. The Lacanian and Heideggerian, rather than Hegelian, interpretation of the Antigone tragedy only serves to show that there is no city to be discovered. This constant 'no' at the heart of every symbolic order cannot found a sociality but only reveal the arbitrariness of creation. This is, on Edelman’s admission, the logic of the radical particularity found in every human, in other words, subjectivism in disguise. Popa’s determinate abolition, on the other hand, opens up a critical space for the political economy critique of actual social relations to release the future in its determination and to found a socialist society.

American exceptionalism

It is almost caricaturistic to see Edelman applying Lacanian theory to the queer theme. One ahistorical structure erected atop another. And yet, the cracks resurface every now and then when Edelman refers to the worn-out distinction between conservative and liberal politics that — alas — we have become too familiar with. The left, for Edelman, is the American liberal left; the right is the American liberal right. Popa knows too well what it is to live in a world that speaks in the language of a culture that never experienced the French Revolution, organized labor, and whose revolution, on Habermas's admission, was never properly modern. Hence, Popa’s dissection of American exceptionalism, its epistemology, and absence of political economy.

Ruins or love?

Edelman gives us a choice: either to “ruin it forever” — to incessantly return to the repetition of the death drive, or — and this is implied — to yield to the worst libertarian tendencies of American life and its exceptionalism. Popa's work offers us a real possibility of a communist future as a productive process based on the determinate critique and negation of existing social relations and human needs. It is not the work of ruin; it is the work of love.

With those conceptual problems and paradoxes in mind, we went on to discuss how queer theory is neglectful of materialism; how Marxist and materialist conception of the body might both challenge and enrich contemporary queer theory; the queerness of carnival; the body fetish in Nazism and fascism; the entanglement of queerness and power; the queering of the body in the context of revolution; socialism as a queering of bodies. We concluded by thinking about different modes of temporality as activities of communist and queer bodies.

The Paradoxes of Soviet Feminism

Our discussion about queerness organically led us to discuss gender and time, which we picked up in our session on late Soviet feminist temporalities. Anya introduced us to a feminist movement that emerged in Leningrad during the 1970s. One of its mouthpieces was the samizdat journal Woman and Russia. Below we recycle a bit from Anya’s insightful introduction to the journal’s aims and its afterlife:

The journal, founded by Tatiana Mamonova and other women writers, aimed to expose the oppression and mistreatment of women in Soviet society, despite the country's progressive laws and apparent empowerment of women. This group of feminist dissidents, part of the "second culture" of Leningrad intellectuals, used their publications to focus on issues such as poor medical care, difficult working conditions, and gender inequalities in the family.

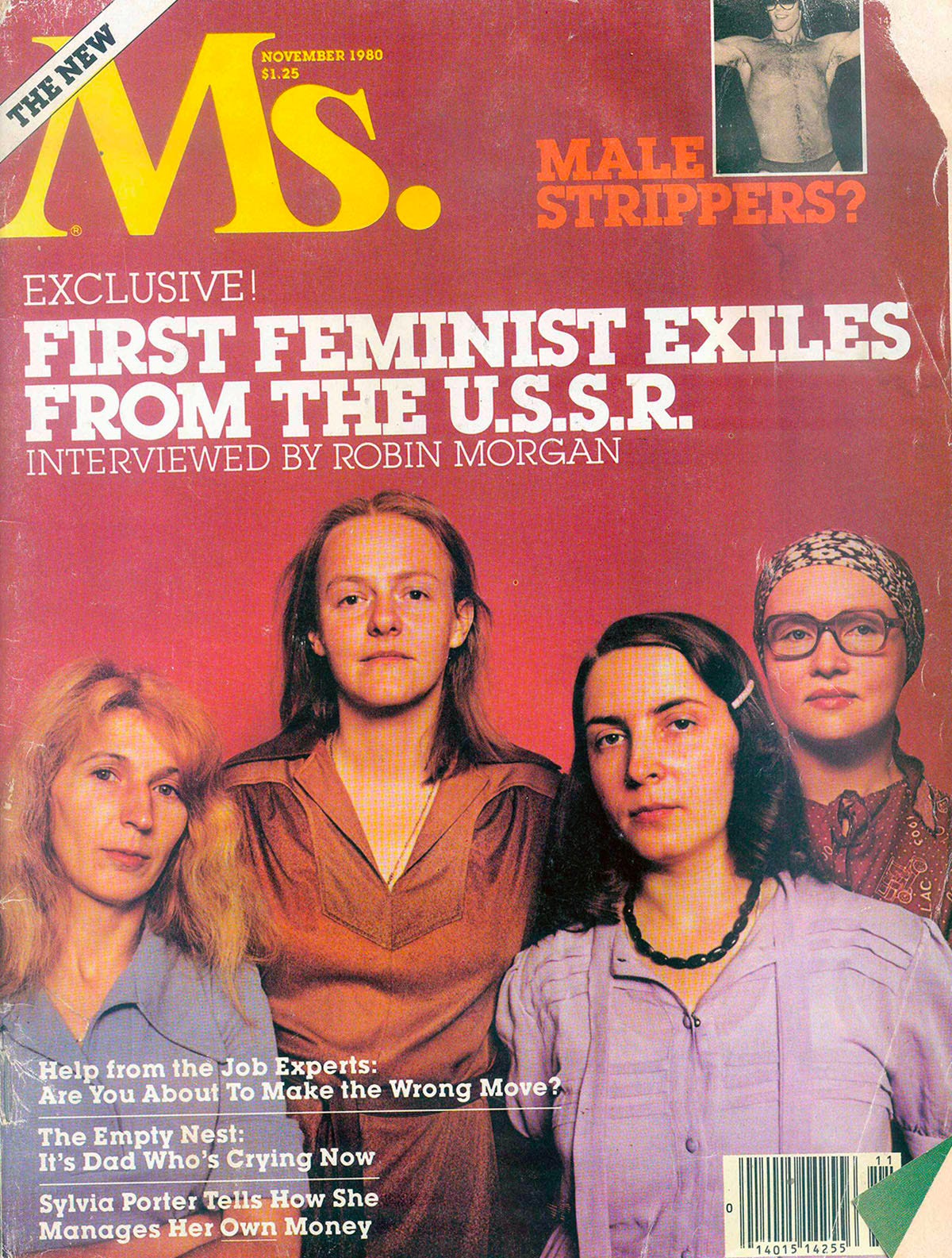

The founders faced rejection from both dissidents and authorities, and after the KGB's intimidation and threats of arrest, the main editorial team was forced to leave the Soviet Union in 1980. Copies of the journal were smuggled to the West, where translations appeared in various countries, revealing the stark contrast between Soviet propaganda and the reality of women's lives. In exile, the feminists continued their activities and engaged with the Western feminist movement to varying degrees. They split into two groups: the Club Maria, which embraced Russian Orthodox Christianity as a path to rediscovering traditional feminine roles, and the more secular Woman and Russia group led by Tatyana Mamonova.

The first essay we read was a piece by Natalia Malakhovskaya from the original samizdat journal. Asya Khodyreva’s essay was included in the re-published 2020 version of the journal that contains comments from contemporary Russian feminist activists and thinkers. Our session discussed the transitions, dialogues and interrupted lines of transmission among three generations of feminisms, from the late 1970s to the early post-Soviet generation until today. How can we describe late Soviet feminism from a contemporary (Western) point of view? What is progressivist about it? What is its legacy today? Our conversation evolved around multiple layers of temporalities, including the relationship between past and present, and Soviet feminism’s relation to tradition and anti-modernity. We discussed the various liberations of women and conceptualised feminist theory as an alternative modernity. We read Malakhovskaya’s presentation of the act of giving birth as unpaid labour along with (Western) feminist social reproduction theory.

Similarly to queer theory being neglectful of materialism, we noted how contemporary feminist theory in the West omits the experience of Soviet feminists. The differences between Eastern and Western feminisms, but also the differences within Soviet feminism itself make it difficult to conceptualise it as one movement. As with many theories which originated in the Global North, so-called “Western” feminism is often not applicable to the diverse experiences of Soviet and post-Soviet women. Yet, those experience could make a valuable contribution to the global struggle of feminist liberation.

What we found most perplexing about some branches of late Soviet feminism was its emphasis on traditional values and religion. The philosopher Tatiana Goricheva’s traditionalist feminism and Club Maria’s liberal democratic Christianity are such examples. Reappropriating Orthodox Christianity and Russianness, Goricheva’s feminist thought generated a paradoxical tension between conservative and progressivist ideas. That version of Soviet feminism was seen by its proponents as revolutionary — a rebellion against perceived Soviet unfreedom by means of a self-chosen return to traditional women’s roles. In this context, we noted that this version of feminism also resonates with and echoes in Aleksandr Dugin’s various takes on gender and queer theory.

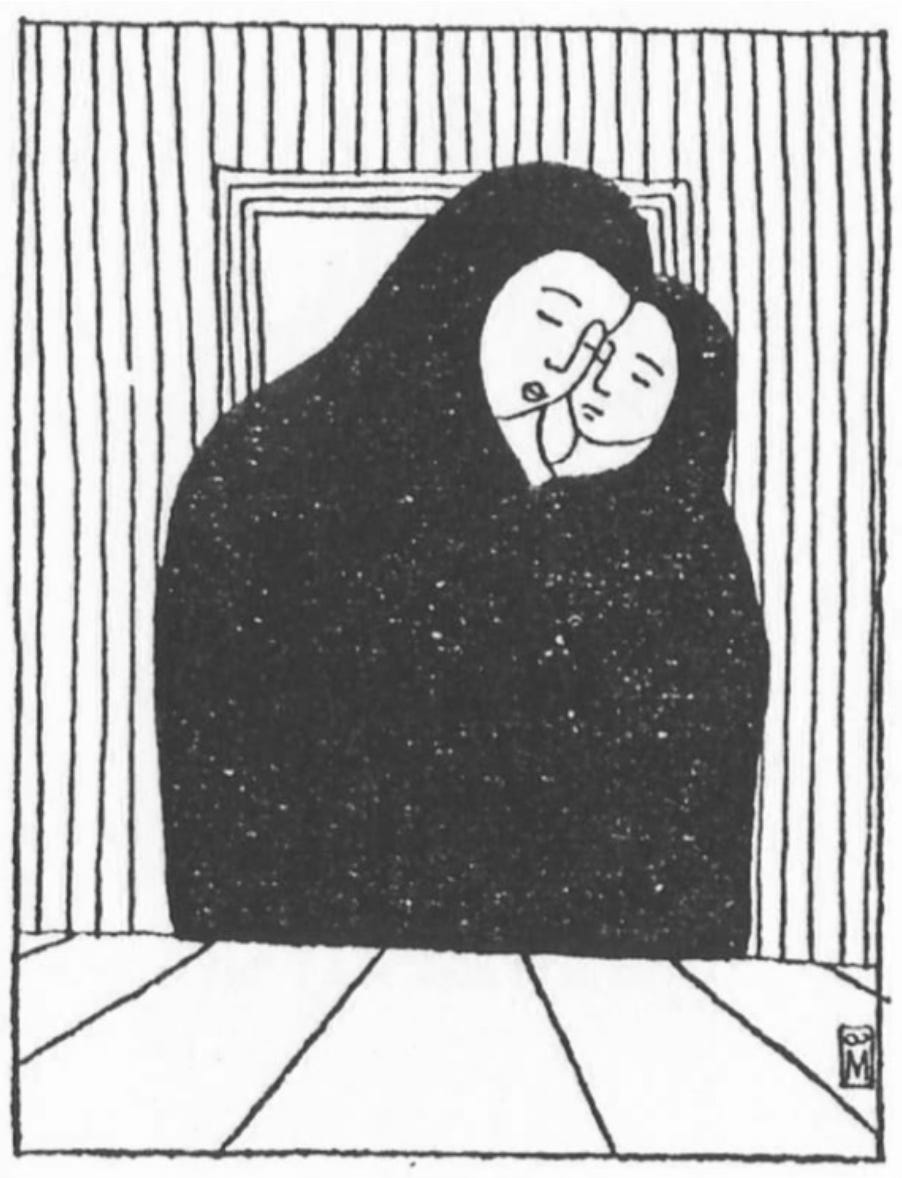

Finally we discussed how Malakhovskaya’s essay presents women as capable of pure love, unlike men who, Malakhovskaya implies, are bound to sexual drive and desire. In this context, we discussed what ‘pure love’ means in a supposedly socialist society. We reflected upon it in terms of wholeness or unity, associated with love in an Orthodox philosophical framework. Any notion of love as total unity implies an abolition of time and a form of stasis or eternity. We finally interrogated the very notion of ‘unity.’ What sort of unity are we talking about? Can unity be a queer concept? What does unity look like from the point of view of women? Is this utopian wholeness a unity of time or a means of transcending history?